Elections: a global ranking rates US weakest among liberal democracies

Defending democracy has suddenly become one of the central challenges of our age. The land war in Ukraine is widely considered a front line between autocratic rule and democratic freedom. The United States continues to absorb the meaning of the riot that took place on January 6 2021 in an attempt to overthrow the result of the previous year’s election. Elsewhere, concerns have been raised that the pandemic could have provided cover for governments to postpone elections.

Elections are an essential part of democracy. They enable citizens to hold their governments to account for their actions and bring peaceful transitions in power. Unfortunately, elections often fall short of these ideals. They can be marred by problems such as voter intimidation, low turnout, fake news and the under-representation of women and minority candidates.

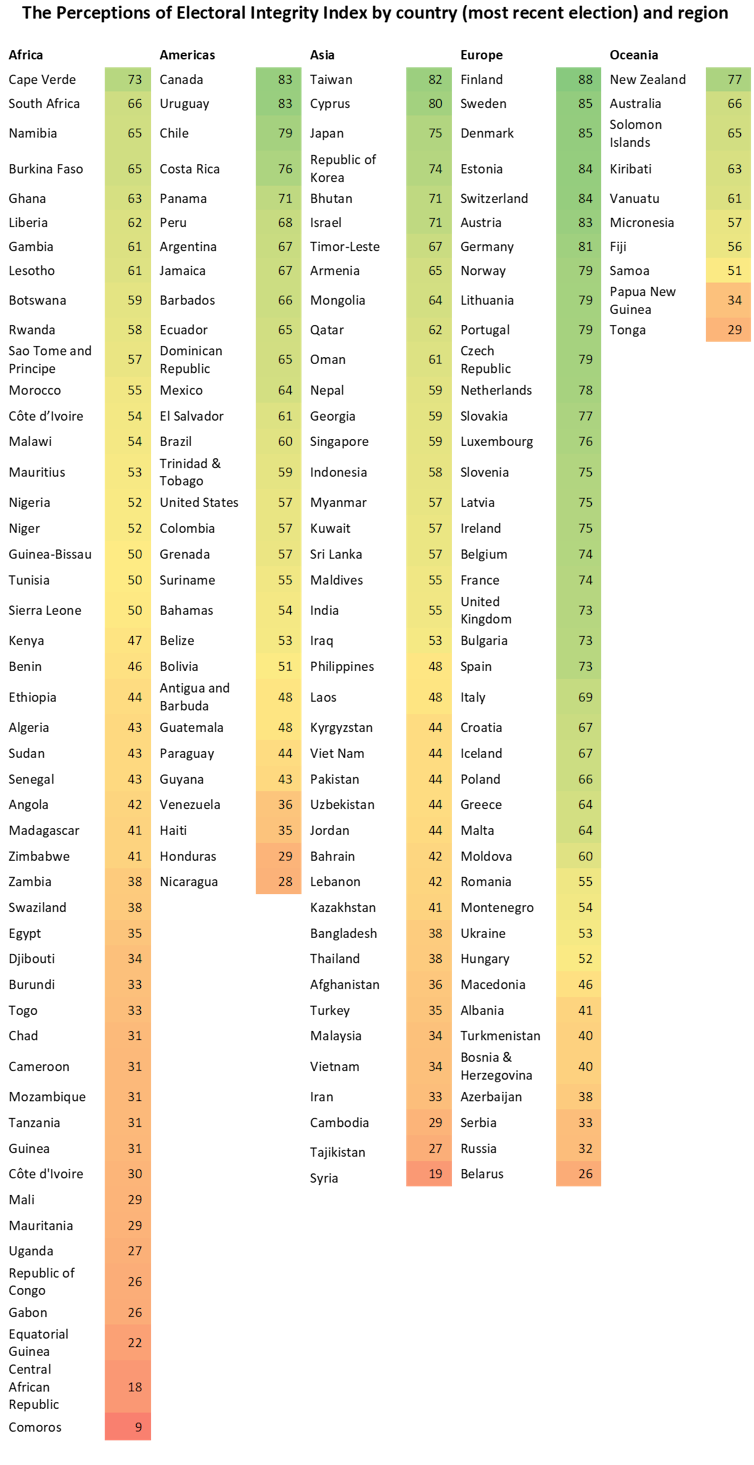

Our new research report provides a global assessment of the quality of national elections around the world from 2012-21, based on nearly 500 elections across 170 countries. The US is the lowest ranked liberal democracy in the list. It comes just 15th in the 29 states in the Americas, behind Costa Rica, Brazil, Trinidad & Tobago and others, and 75th overall.

Why is the United States so low?

There were claims made by former president Donald Trump of widespread voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election. Theses claims were baseless, but they still caused the US elections ranking to fall.

Elections with disputed results score lower on our rankings because a key part of democracy is the peaceful transition of power through accepted results, rather than force and violence. Trump’s comments led to post-election violence as his supporters stormed the Capitol building and sowed doubt about the legitimacy of the outcome amongst much of America.

This illustrates that electoral integrity is not just about designing laws – it is also dependent on candidates and supporters acting responsibly throughout the electoral process.

Problems with US elections run much deeper than this one event, however. Our report shows that the way electoral boundaries are drawn up in the US are a main area of concern. There has been a long history of gerrymandering, where political districts are craftily drawn by legislators so that populations that are more likely to vote for them are included in a given constituency – as was recently seen in North Carolina.

Voter registration and the polls is another problem. Some US states have recently implemented laws that make it harder to vote, such as requiring ID, which is raising concern about what effect that will have on turnout. We already know that the costs, time and complexity of completing the ID process, alongside the added difficulties for those with high residential mobility or insecure housing situations, makes it even less likely that under-represented groups will take part in elections.

Nordics on top, concern about Russia

The Nordic countries of Finland, Sweden and Denmark came out on top in our rankings. Finland is commonly described as having a pluralistic media landscape, which helps. It also provides public funding to help political parties and candidates contest elections. A recent report from the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights found a “high level of confidence in all of the aspects of the electoral process”.

Cape Verde has the greatest quality of electoral integrity in Africa. Taiwan, Canada and New Zealand are ranked first for their respective continents.

Electoral integrity in Russia has seen a further decline following the 2021 parliamentary elections. A pre-election report warned of intimidation and violence against journalists, and the media “largely promote policies of the current government”. Only Belarus ranks lower in Europe.

Globally, electoral integrity is lowest in Comoros, the Central African Republic and Syria.

Money matters

How politicians and political parties receive and spend money was found to be the weakest part of the electoral process in general. There are all kinds of threats to the integrity of elections that revolve around campaign money. Where campaign money comes from, for example, could affect a candidate’s ideology or policies on important issues. It is also often the case that the candidate who spends the most money wins – which means unequal opportunities are often part and parcel of an election.

It helps when parties and candidates are required to publish transparent financial accounts. But in an era where “dark money” can be more easily transferred across borders, it can be very hard to trace where donations really come from.

There are also solutions for many of the other problems, such as automatic voter registration, independence for electoral authorities, funding for electoral officials and electoral observation.

Democracy may need to be defended in battle, as we are currently seeing in Ukraine. But it also needs to be defended before it comes to all-out conflict, through discussion, protest, clicktivism and calls for electoral reforms.![]()

Toby James, Professor of Politics and Public Policy, University of East Anglia and Holly Ann Garnett, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Royal Military College of Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.